| Features: Garden wildlife |  |

Living with Mammals As a species, humans are builders: from bivouacs to great conurbations, we transform the world around us. Housing, infrastructure and recreational spaces create new habitats and destroy others, and the green spaces within our towns, whether managed or left wild, blur the boundary between natural and urban landscapes. These spaces support unique communities of wildlife. They offer an alternative way of life for species such as the fox and can act as 'green corridors', linking habitats that are too small to support communities alone.

As a species, humans are builders: from bivouacs to great conurbations, we transform the world around us. Housing, infrastructure and recreational spaces create new habitats and destroy others, and the green spaces within our towns, whether managed or left wild, blur the boundary between natural and urban landscapes. These spaces support unique communities of wildlife. They offer an alternative way of life for species such as the fox and can act as 'green corridors', linking habitats that are too small to support communities alone.

Mammal Trust UK's annual survey of these spaces, Living with Mammals, begins its fifth survey season in 2007 Mammal Trust UK's annual survey of these spaces, Living with Mammals, begins its fifth survey season in 2007 Mammal Trust UK's annual survey of these spaces, Living with Mammals, begins its fifth survey season in 2007 and has shown that, when we take the time to look, it can be surprising who we find our neighbours are. Mammal Trust UK's annual survey of these spaces, Living with Mammals, begins its fifth survey season in 2007 and has shown that, when we take the time to look, it can be surprising who we find our neighbours are.

A growing urban patchwork Muntjac Deer in a garden.Living with Mammals defines the built environment as that within 220 yards (200m) of buildings, whether in a rural or urban setting, but is in the latter that most people are likely to encounter wildlife from day to day. Muntjac Deer in a garden.Living with Mammals defines the built environment as that within 220 yards (200m) of buildings, whether in a rural or urban setting, but is in the latter that most people are likely to encounter wildlife from day to day.  Ten percent of the land cover of the UK is urban and it is home to 80 percent of the population Ten percent of the land cover of the UK is urban and it is home to 80 percent of the population Ten percent of the land cover of the UK is urban and it is home to 80 percent of the population. Ten percent of the land cover of the UK is urban and it is home to 80 percent of the population.

Several factors have driven the growth of the built environment: as the number of households increases, so the demand for housing has grown, and socio-economic changes have driven the spread of recreational land (such as playing fields and golf courses) and 'transport corridors' (roads and railways). Scotland's population of around five million, for example, has changed little in size between 1940 and 1990 but the number of households has increased by 40 percent during this time. The area of built land has grown by almost half, largely replacing farmland.

Particularly important in this respect, are gardens.  Private gardens collectively cover about 667,000 acres (270,000 hectares) in Britain and make up the largest urban green space Private gardens collectively cover about 667,000 acres (270,000 hectares) in Britain and make up the largest urban green space Private gardens collectively cover about 667,000 acres (270,000 hectares) in Britain and make up the largest urban green space as well as the largest single category of site in Living with Mammals. An important feature of urban areas though is the mix of habitats which make them up: as well as domestic gardens, allotments, amenity grassland, industrial estates, derelict ground, and areas of heath and woodland may all be part of the mix. As the built environment grows and as wild habitats become scarcer, our towns and cities may be becoming increasingly important to wildlife. Private gardens collectively cover about 667,000 acres (270,000 hectares) in Britain and make up the largest urban green space as well as the largest single category of site in Living with Mammals. An important feature of urban areas though is the mix of habitats which make them up: as well as domestic gardens, allotments, amenity grassland, industrial estates, derelict ground, and areas of heath and woodland may all be part of the mix. As the built environment grows and as wild habitats become scarcer, our towns and cities may be becoming increasingly important to wildlife.

And wildlife, in turn, is important to us. The value of the our natural environment is talked about today in terms of 'ecosystem services', the benefits of clean water sources, natural flood defences or soil formation, for example. The value of the green spaces in our built environment to many people is the link with wildlife that they provide, the enjoyment of watching fox cubs playing or bats darting overhead. The aesthetic value of our environment is difficult to value in monetary terms but its importance, and the contribution of biodiversity to it, is formally recognised in the government's quality of life indicators.

Wood mouse taking food from a garden feeding station (Copyright Vera Rhodes).

If this biodiversity is to be fostered, we need to know which habitats encourage species into the built landscape and which exclude them. Wood mouse taking food from a garden feeding station (Copyright Vera Rhodes).

If this biodiversity is to be fostered, we need to know which habitats encourage species into the built landscape and which exclude them.  Living with Mammals is the first national scheme to survey sites across a range of near-urban habitats, from railway embankments to waterways, recording sightings and field signs of mammals through April, May and June Living with Mammals is the first national scheme to survey sites across a range of near-urban habitats, from railway embankments to waterways, recording sightings and field signs of mammals through April, May and June Living with Mammals is the first national scheme to survey sites across a range of near-urban habitats, from railway embankments to waterways, recording sightings and field signs of mammals through April, May and June. Of the different types of site, gardens make-up the largest group, accounting for four-fifths of sites. They provide a range of microhabitats (such as lawns, ponds, compost heaps and woodpiles) that can support rich invertebrate communities, and additional sources of food (such as vegetable patches and bird feeders). In addition, they provide nesting sites and hibernacula, and in this respect, buildings are particularly important. Bats, grey squirrels and pine martens can be found in roof spaces, and foxes and hedgehogs frequently make use of spaces under garden sheds. Living with Mammals is the first national scheme to survey sites across a range of near-urban habitats, from railway embankments to waterways, recording sightings and field signs of mammals through April, May and June. Of the different types of site, gardens make-up the largest group, accounting for four-fifths of sites. They provide a range of microhabitats (such as lawns, ponds, compost heaps and woodpiles) that can support rich invertebrate communities, and additional sources of food (such as vegetable patches and bird feeders). In addition, they provide nesting sites and hibernacula, and in this respect, buildings are particularly important. Bats, grey squirrels and pine martens can be found in roof spaces, and foxes and hedgehogs frequently make use of spaces under garden sheds.

Biodiversity on our doorstep

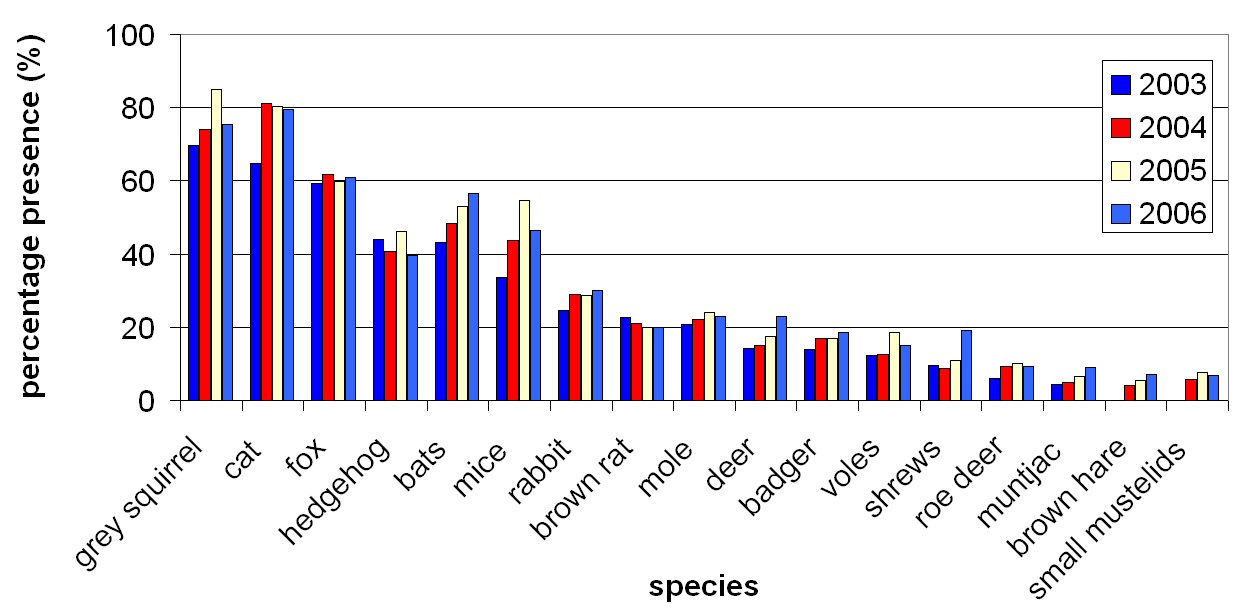

Around half of Britain's terrestrial wild mammals have been recorded in the survey (in total, 30 species or groups of species, such as bats, have been spotted), highlighting the importance of such habitats to biodiversity. Some, such as mice and rats, have been our living companions around the world for millennia, while others such as grey squirrels and red foxes are comparatively recent urban dwellers.

Grey squirrels are as ubiquitous as domestic cats in the built environment, turning-up at three-quarters of the sites that were surveyed. Grey squirrels are as ubiquitous as domestic cats in the built environment, turning-up at three-quarters of the sites that were surveyed.

Foxes began to colonise suburban areas of London in the 1930s and caught the public eye in the early 1960s. Today, there are thought to be about 5,000 foxes within the M25, and perhaps seven times as many in urban areas nationally. In cities, foxes typically have home ranges of 50 to 100 acres (20 to 40 hectares), about a tenth of the size of those in farmland areas and take advantage of a wide range of food sources: earthworms, insects, fruit, wild animals and pets are all on the menu. Inner city foxes tend to eat less caught prey than those in the suburbs, feeding more on scavenged food. There are also foxes that enjoy the pickings of the town while living in rural areas, commuting in at night to forage.

Sixty percent of sites in the survey reported sightings or signs of foxes.

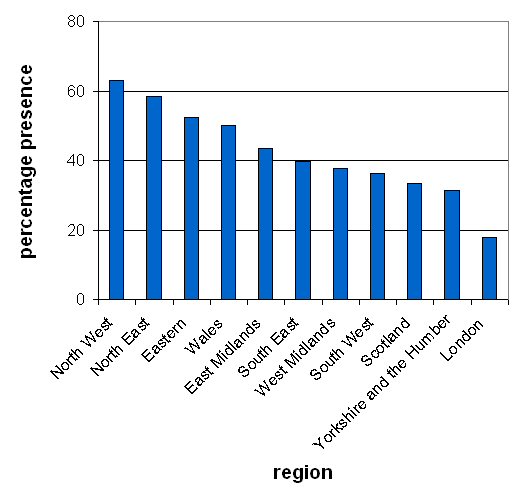

Many of the species recorded in Living with Mammals are of conservation concern Many of the species recorded in Living with Mammals are of conservation concern Many of the species recorded in Living with Mammals are of conservation concern; these are species that it is thought should be monitored where possible. Hedgehogs were one of the most frequently encountered of these, present at about 40 percent of the surveyed sites. Hedgehogs, however, may be less common in gardens now than they once were; regeneration of brownfield sites, 'urban fill' and the use of pesticides are likely to have had a negative impact, but it is still uncertain how their numbers are changing. Sites in the north and eastern areas of England were more likely to record hedgehogs than those in London, a particularly urbanised region. Though hedgehogs can do well in urban gardens, such sites may be an inaccessible habitat for hedgehogs if few 'green corridors' link individual sites. Many of the species recorded in Living with Mammals are of conservation concern; these are species that it is thought should be monitored where possible. Hedgehogs were one of the most frequently encountered of these, present at about 40 percent of the surveyed sites. Hedgehogs, however, may be less common in gardens now than they once were; regeneration of brownfield sites, 'urban fill' and the use of pesticides are likely to have had a negative impact, but it is still uncertain how their numbers are changing. Sites in the north and eastern areas of England were more likely to record hedgehogs than those in London, a particularly urbanised region. Though hedgehogs can do well in urban gardens, such sites may be an inaccessible habitat for hedgehogs if few 'green corridors' link individual sites.

Few surveys of urban hedgehogs exist and currently only Living with Mammals and the British Trust for Ornithology's Garden BirdWatch collect data on garden populations. Over time, the findings of these surveys can build a clearer picture of how hedgehogs - a much-loved icon of our natural history - are faring.

The percentage of sites in different regions that recorded hedgehogs. The percentage of sites in different regions that recorded hedgehogs.

Bats, shrews and badger were among the other protected species recorded, as well as six species- common pipistrelle, brown hare, water vole, hazel dormouse, otter and red squirrel - that are 'Priority Species', those for which action plans have been developed as part of the UK Biodiversity Action Plan (UK BAP), an internationally recognised programme of targeted measures to protect threatened species and habitats. Although the urban environment does not have a national action plan within the UK BAP, a "habitat statement" and a number of local action plans recognise its importance to biodiversity.

One trend suggested by the results to date is an increase in the proportion of sites that are home to bats. The most abundant British bat, and one that is found in urban environments, is the common pipistrelle, which often roosts in buildings, beneath tiles or under roofing felt. The percentage of sites recording bats in Living with Mammals has risen each year of the survey and this has mirrored the findings of a recent survey by the Bat Conservation Trust. In contrast to Living with Mammals, the BCT survey recorded pipistrelles in randomly chosen 1km squares in the landscape as a whole. Between 1998 and 2005, the proportion of positive squares showed an average annual increase of eight percent. The similar rise found in Living with Mammals suggests that, as the population expands, individuals are taking advantage of the benefits of urban sites.

As long-term trends emerge, so it is hoped that its findings can feed into local action plans and that, with the help of gardeners, we may see more of our mammal neighbours.

| First published March 2007. | |

Copyright David Wembridge 2007. Permission is hereby granted for anyone to use this article for non-commercial purposes which are of benefit to the natural environment as long the original author is credited. School pupils, students, teachers and educators are invited to use the article freely. Use for commercial purposes is prohibited unless permission is obtained from the copyright holder. |

Back to home page

Do you live in Merseyside? Interested in its wildlife? | |